Merging eight websites into one

How can we replace eight websites with one- and make sure no one gets lost?

Business analyst

Product manager

Developers

Background

On April 1, 2023, seven district councils and one county council merged into a single authority. One of the key projects in this convergence was building a new website—a day-one deliverable that would unify the information from eight separate council websites.

As part of this redesign, I was tasked with evaluating the homepage navigation, particularly for paid services, and refining the information architecture behind them. This project was an opportunity to help shape the future of a website that would serve as the front door for over 600,000 residents.

At the outset, I was eager to explore how language and structure impact usability, ensuring residents could find and access the services they needed. However, I quickly realised that this project would evolve in unexpected ways—calling for adaptability and problem-solving beyond what I had initially anticipated.

The first iteration of the homepage design carried over elements from the county council website, including the seemingly straightforward "My Account" button and category labels such as "Apply," "Book," "Pay," and "Report". These labels had gone largely unchallenged... until we started mapping out what content would sit behind each one.

Process

I use the Design Thinking framework as a foundation: empathise > define > ideate, prototype, test - always starting with user and client empathy. After that, the rest of the process is rarely linear. It’s a dynamic journey—iterating on designs, adapting to shifting stakeholder needs, and navigating platform or resource constraints. Projects often loop back before moving forward before delivering an intuitive and user-friendly product.

Taking stock of what we have

By the time I joined the project, the website had already been designed, and I was brought in to to refine the homepage navigation. To begin the empathise and define phases, I immersed myself in the eight original websites and the new design prototype, uncovering how users had previously accessed services.

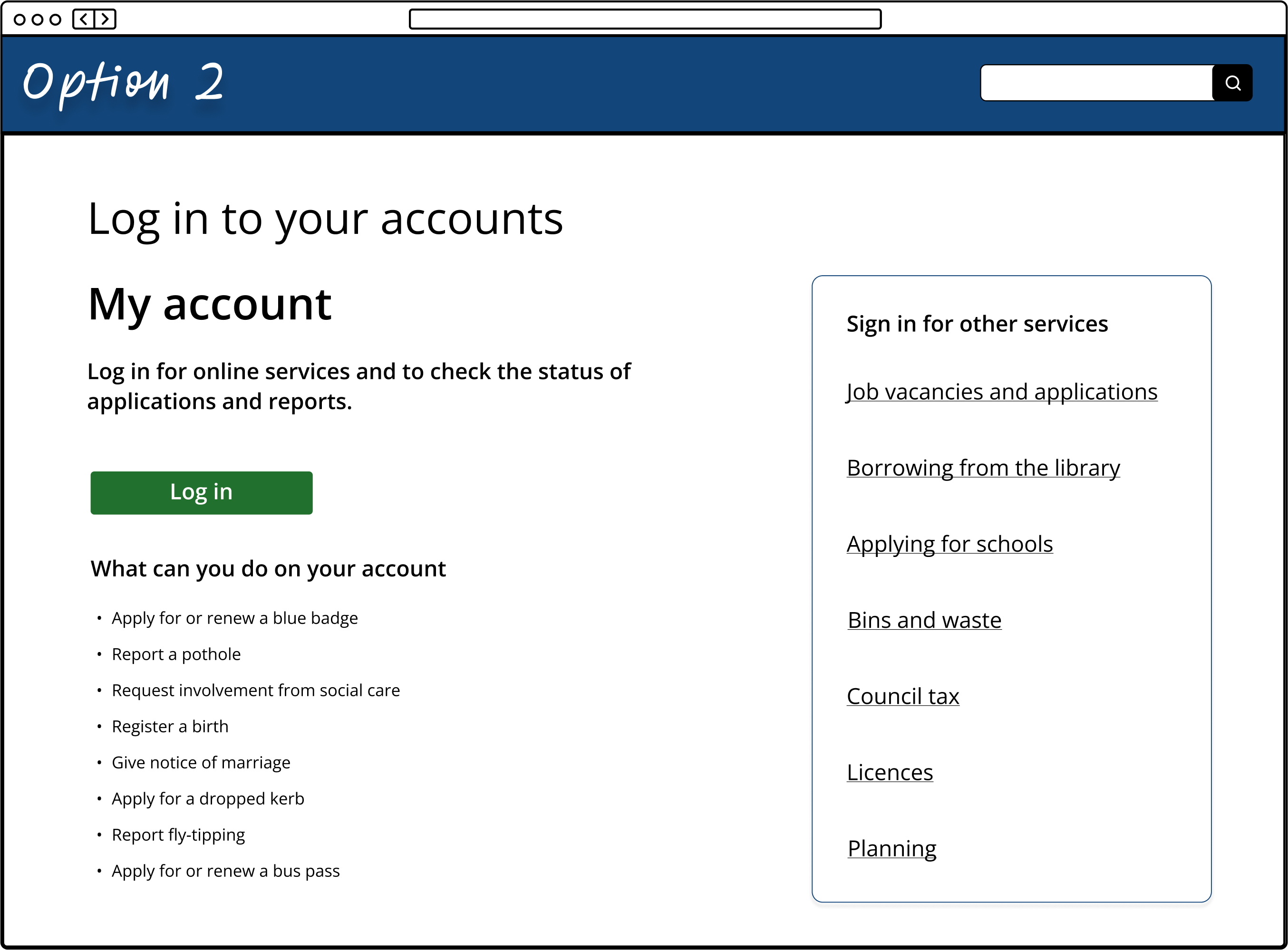

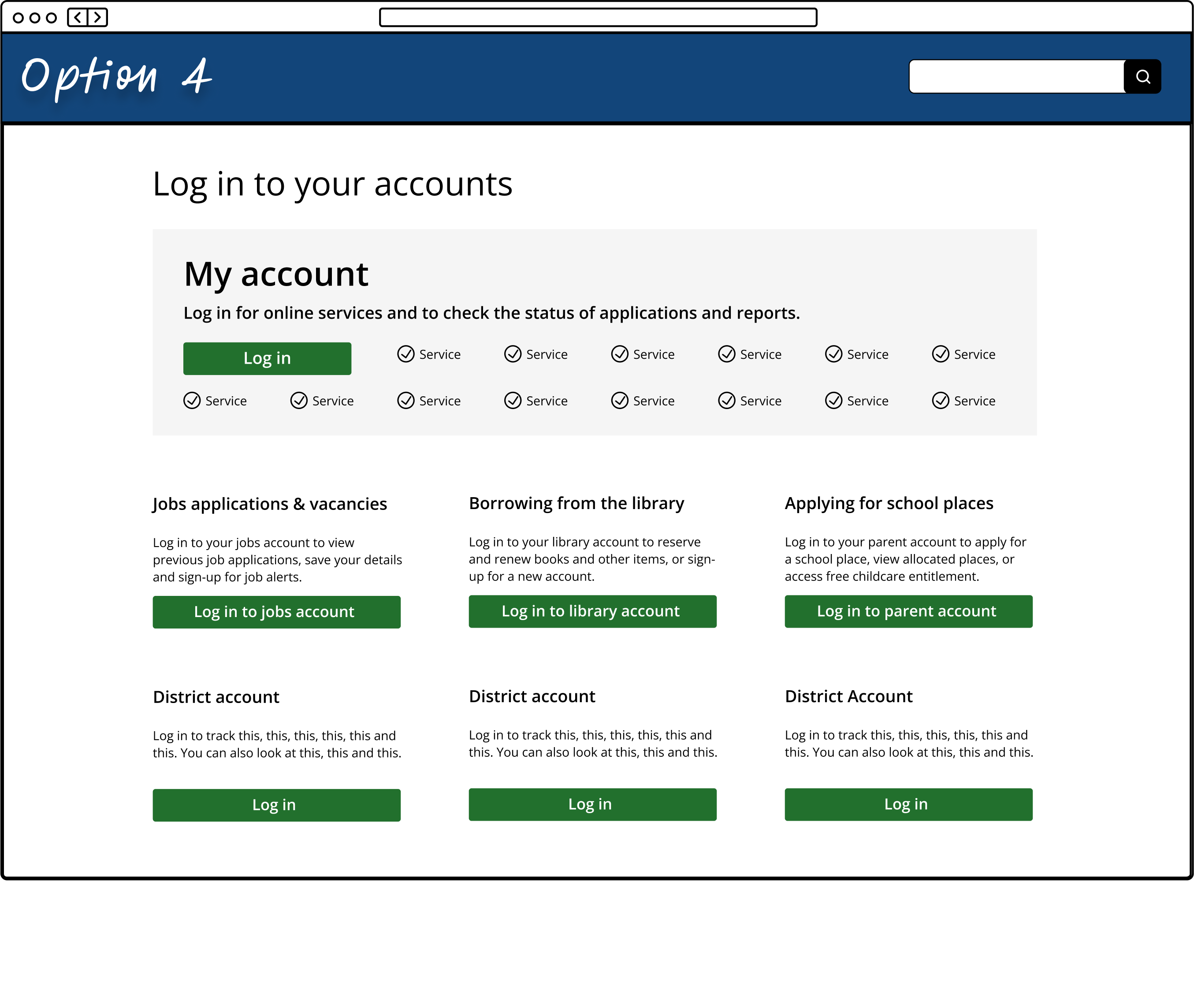

As one of the tasks was looking at the “My account” button, this became my first point of focus. I was briefed that while the county council had multiple “My account” options, only five of the seven districts offered any account functionality at all. To understand the broader landscape, I also reviewed numerous other local authority websites, exploring how they approached account-based services for their residents.

Number of accounts available for each council:

- County council: 4

- District council A: 2

- District council B: 1

- District council C: 0

- District council D: 2

- District council E: 0

- District council F: 2

- District council G: 1

A “My account” button in the top right corner sounds reasonable right?

The complications didn’t end with the number of accounts each council offered—what those accounts provided varied just as much.

At the former county council, we had a general account, a library account, a parents’ account, and a jobs account.

Meanwhile, district councils had their own versions, ranging from waste services to council tax to planning applications. Every district offered the same core services, but no two handled online access in the same way.

The problem was clear.

The new website design had featured a single “My account” button in the top-right corner. But with so much variation, how could we guide users to the right account? How would they know which one to check for bin collection dates and which one to use to report a pothole?

And once they figured out what they needed, how would we direct them to their district’s version—while still presenting a unified council experience?

Eliminating all existing accounts wasn’t an option. Full convergence of services and CRM (customer relationship management) systems was projected to take at least five years. The question was: what could we do for day one?

Optimistically, I proceeded with ideation

I kicked off the ideation phase by sketching out different ways to guide users after they selected the (now infamous) “My account” button. Each version took a slightly different approach to organizing the accounts, aiming to make navigation clearer. I explored:

- Grouping accounts by location

- Organising them by service or action (e.g., reporting an issue, checking payments)

- Highlighting top tasks users frequently accessed

- A combination of these approaches

Despite these efforts, when I shared the concepts with the product team, the reaction was unanimous—it was still too confusing. Rather than simplifying the experience, we risked sending users in the wrong direction or leading them to frustrating dead ends.

We needed a different approach.

We suggested an (somewhat radical) idea

To create a more user-friendly experience and reduce confusion, we proposed something unexpected: removing the “My account” button and page entirely. It was a bold suggestion—one that surprised stakeholders and was met with hesitation from those who had accepted its presence. But we had the data to back it up.

Google Analytics (GA4) revealed that most users weren’t navigating to their accounts from the homepage. Instead, they were starting their journey with a Google search, landing directly on the specific service page they needed. We considered why someone might need to access their account and how they typically got there.

If a user wanted to report an issue—like a pothole—they weren’t searching for their account first. Instead, they were finding the highways page, launching the report form, and only then logging in. Similarly, if they needed to check the status of a blue badge application, they were first looking for the blue badge information page, then accessing their account from there.

While some users would always prefer to access their account directly, displaying multiple accounts with different functions on a single page created more confusion than clarity. The benefits of removing the button outweighed those of keeping it.

Of course, the only way to be certain was to test. Hold that thought.

The other buttons

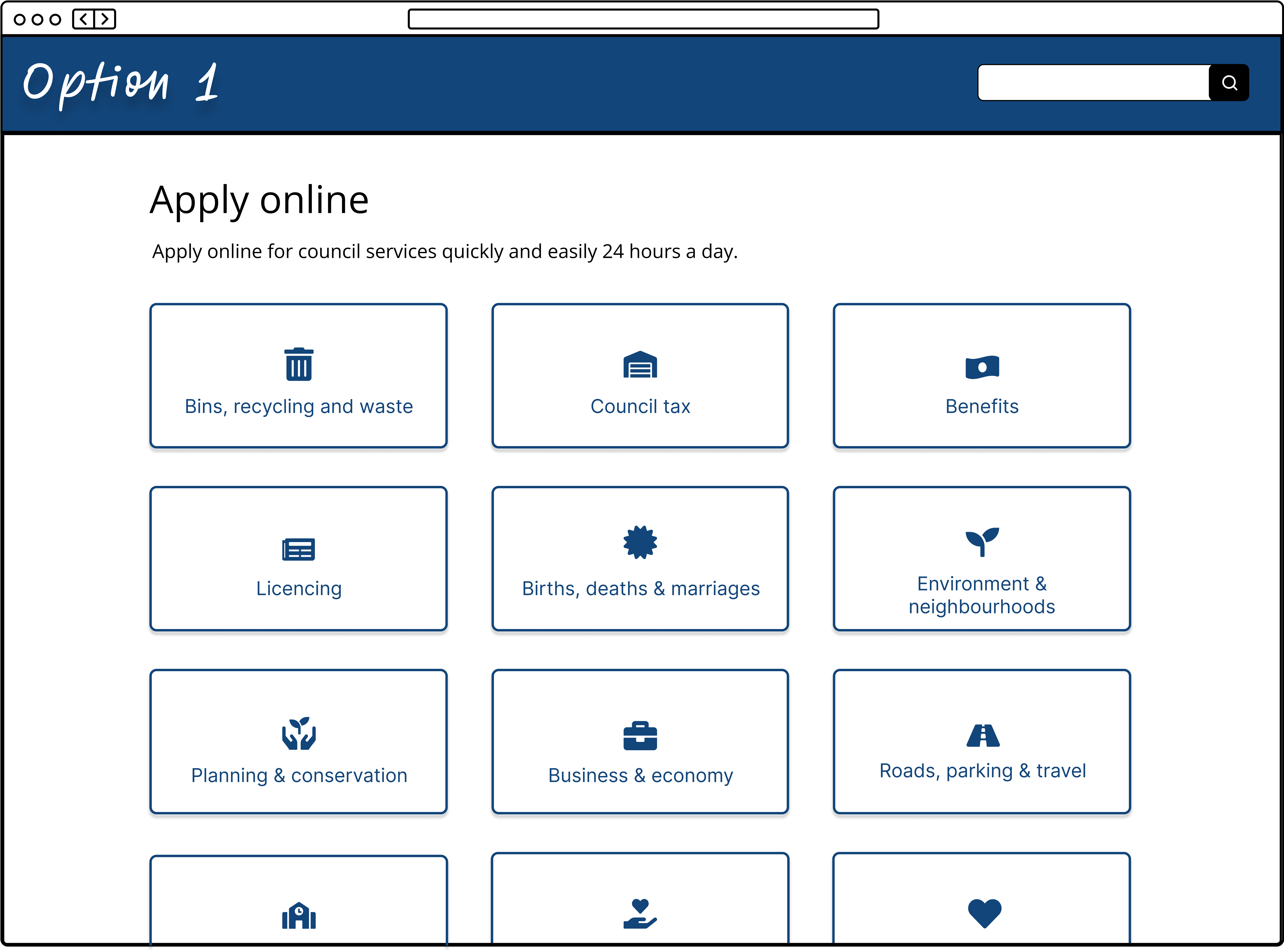

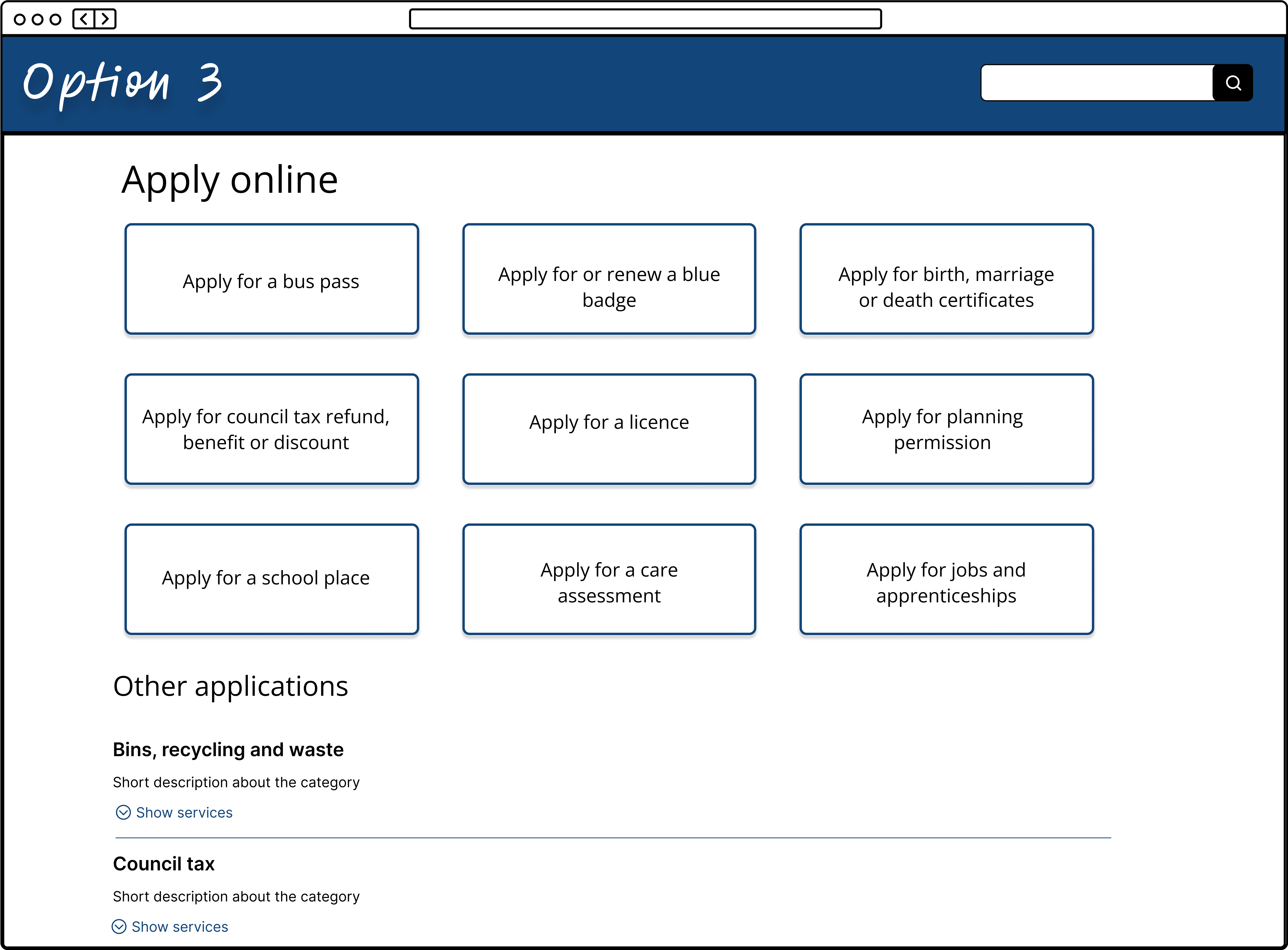

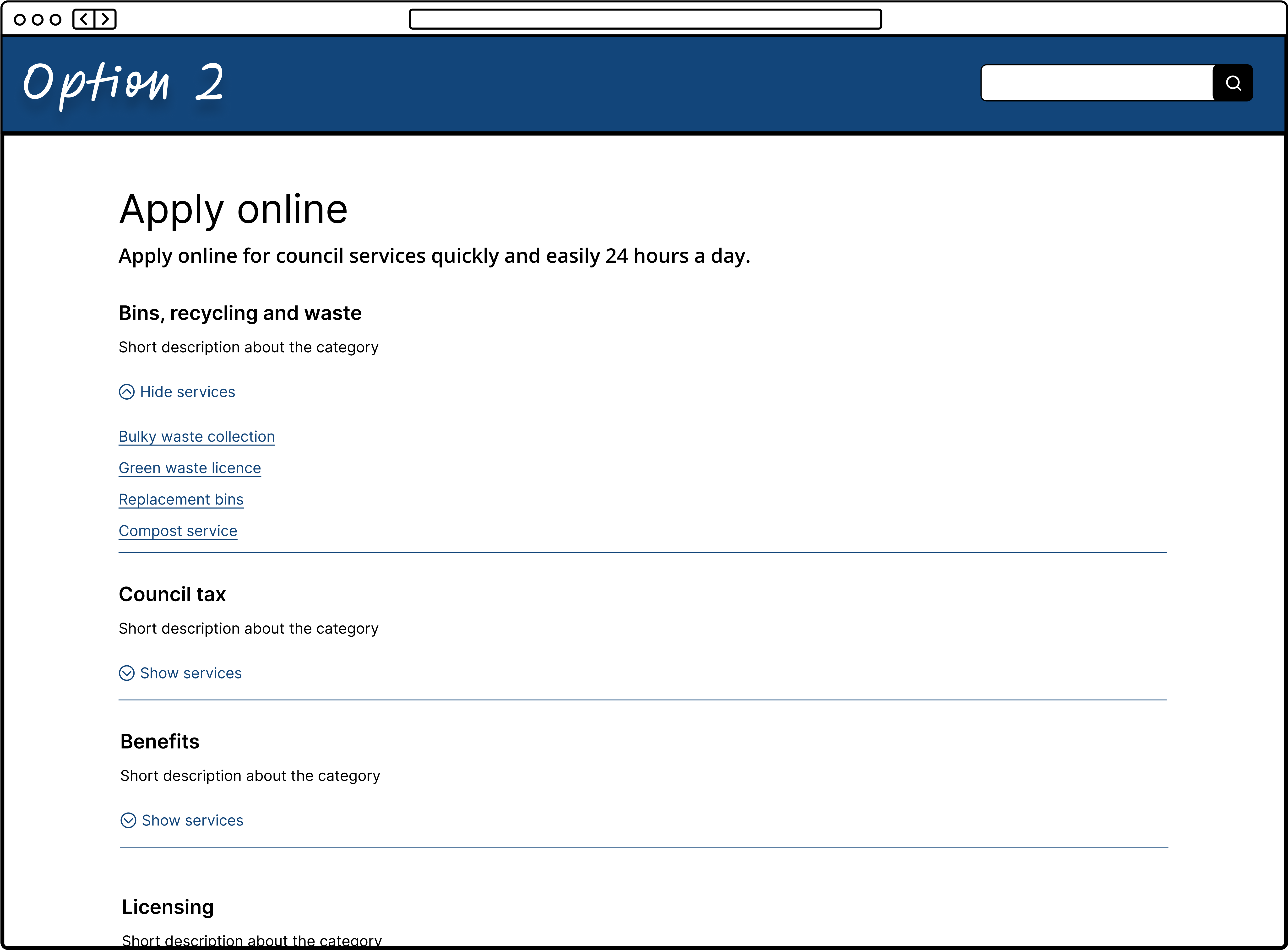

Another key area of the homepage navigation I was tasked with was the "Apply," "Book," "Pay," and "Report" buttons. These had been carried over from the original county council website and were intended to direct users to online service forms. My role was to design how the pages behind each button would be structured and presented.

However, when reviewing all eight websites, I uncovered significant inconsistencies. What one district categorized under "Pay," another placed under "Book." If an application required a payment, would users look under "Apply" or "Pay"? These weren’t just inconsistencies across the councils—this was a deeper issue of language ambiguity that likely confused users on the original websites as well.

The problem was clear: the “Apply,” “Book,” “Pay,” and “Report” buttons had low information scent—they didn’t provide enough context for users to confidently choose the right path. This lack of clarity would increase cognitive load and frustration, making it harder for people to find what they needed.

On top of the language inconsistencies, there was another challenge—each district offered different levels of online service access. We weren’t just dealing with hundreds of services; we were dealing with up to eight different ways of delivering each one.

Again, I optimistically proceeded with ideation

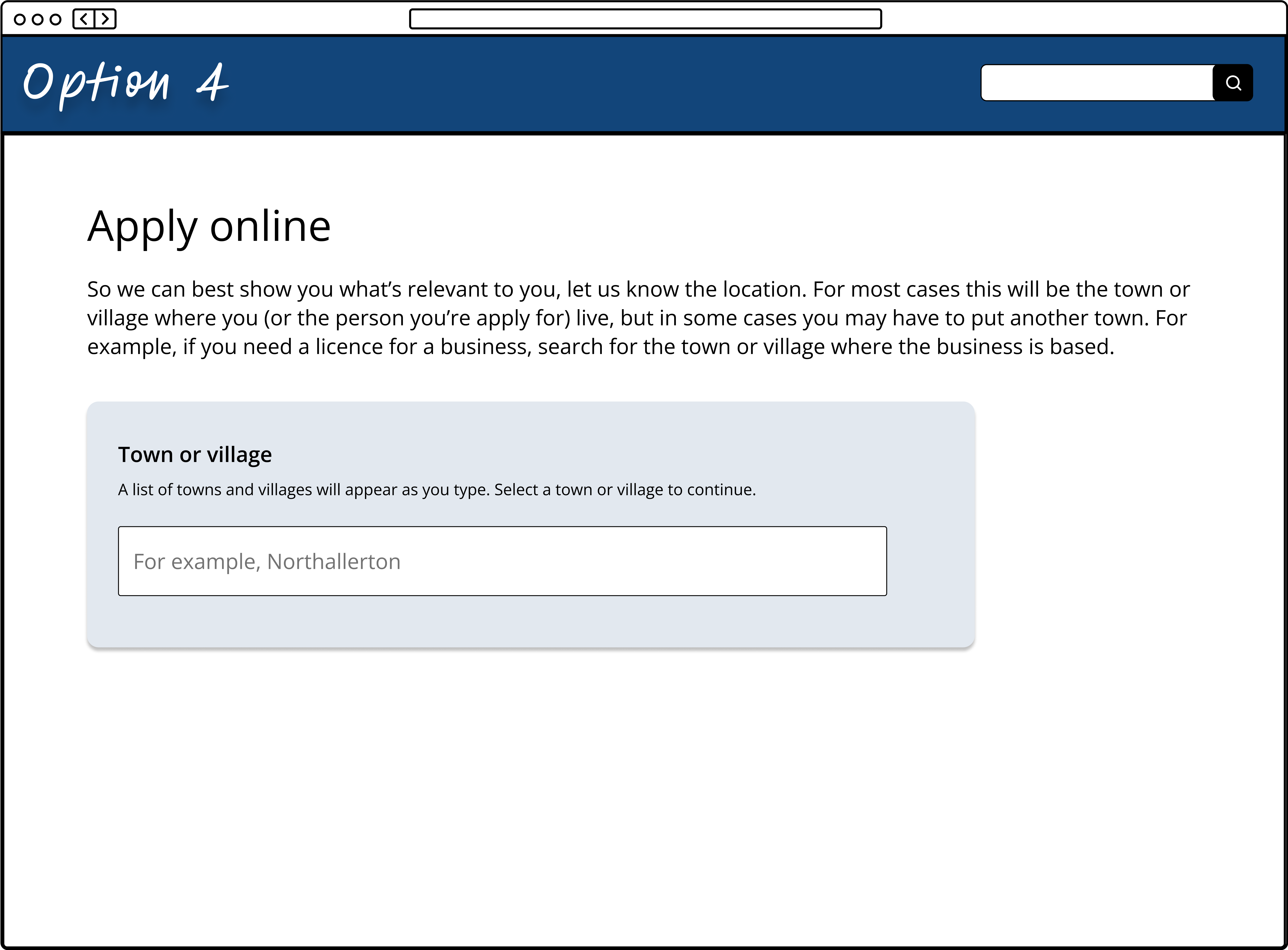

I explored countless variations, including:

- Splitting "Apply" options into categories

- Highlighting top tasks related to applying for services

- A location-first approach to guide users based on their district

But when I presented these ideas to the product team, none felt quite right. We realised that structuring the pages behind these buttons essentially created an entirely new information architecture—one that overlapped with the existing homepage categories.

If users were already on the homepage, they should ideally navigate through the primary categories rather than detour into an "Apply," "Book," "Pay," or "Report" section, only to be faced with another layer of categorisation. However, removing categories entirely wasn’t a solution either—a single, unstructured list would be far too long to scan effectively.

This reinforced the need to rethink whether these buttons were helping or hindering users in their journey.

The (now less radical) idea popped up again

You probably saw this coming—it was time to test removing the “Apply,” “Book,” “Pay,” and “Report” buttons too.

Just like with the “My account” button, analytics data suggested these buttons weren’t heavily used. As long as users could still find what they needed seamlessly, removing them seemed like the logical next step. Now, the question was: Would their absence improve navigation or create new friction? Testing would give us the answer.

Time to test

Two days, 17 participants, and countless insights.

Armed with chocolate biscuits, a colleague and I set up a testing area in one of our local offices. We were fortunate to have 17 enthusiastic volunteers ready to help us test the navigation of the new website. All sessions were in-person and moderated, with me facilitating and my colleague taking notes.

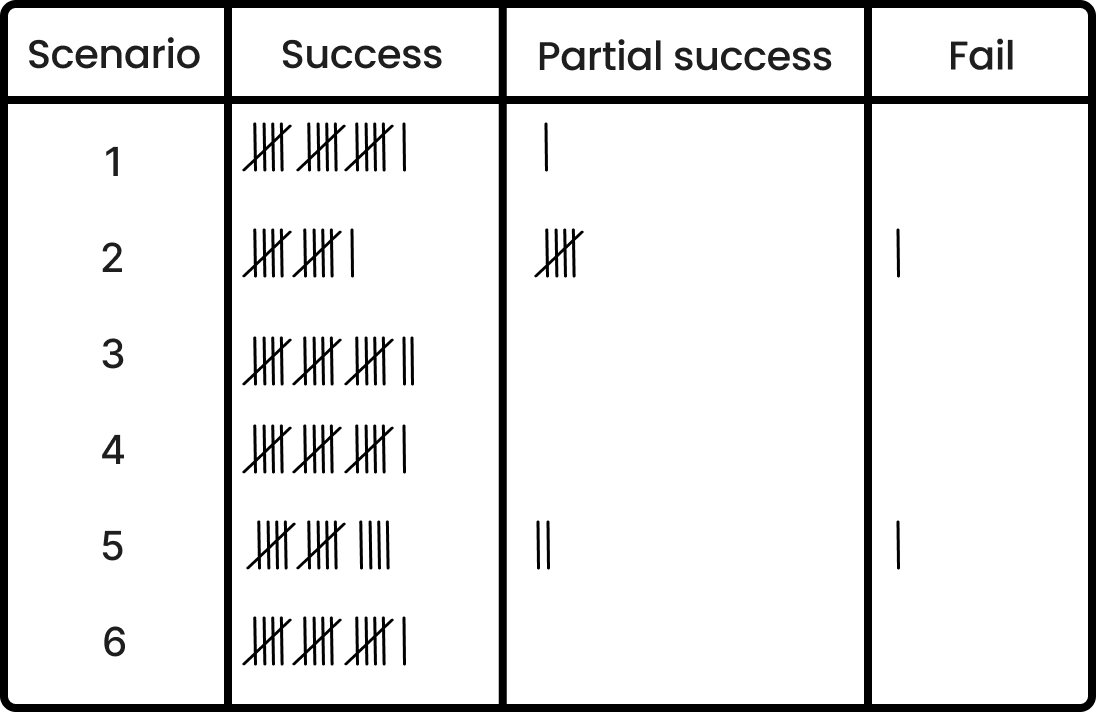

We designed six real-world scenarios, each reflecting a common user task that would have previously relied on the now-removed buttons. Each scenario required participants to either log into an account or complete an action that had once been categorized under "Apply," "Book," "Pay," or "Report" on the original website.

To ensure unbiased results, we framed each scenario in an open-ended way, avoiding leading participants toward a specific path. For example, instead of directly instructing them to log in, we asked them to check the status of a recent secondary school place application for their child. This task naturally required accessing their "parents" account, allowing us to observe how they navigated to it without the crutch of a "My account" button.

In theory, we were confident in the design, but some stakeholders remained sceptical.

The testing results spoke for themselves—users successfully completed their tasks 90% of the time, reinforcing that the removal of the “My Account,” “Apply,” “Book,” “Pay,” and “Report” buttons had no negative impact on navigation.

This was also the first time the new website had been tested with real users. Since our scenarios reflected common user actions, the high success rate was a reassuring sign that we were launching with a website that was intuitive and easy to use from day one.

Outcome

After presenting our test findings, stakeholders were confident in the decision to move forward without the “My Account,” “Apply,” “Book,” “Pay,” and “Report” buttons.

While the outcome wasn’t what anyone had initially expected, the team remained open to challenging assumptions and adapting based on real user insights. This project served as a valuable reminder not to take design elements for granted—every feature should have a clear, evidence-based purpose.

With these insights guiding our decisions, the new website launched smoothly on day one, setting a strong foundation for the future.

Impact

To ensure we stayed on the right track, we continuously monitored customer feedback, Net Promoter Score (NPS) responses, and search term data from Google Analytics (GA4).

The feedback was largely positive, and the absence of frequent searches for "My Account" reinforced our confidence in the decision. Users were finding what they needed without the removed buttons, validating our approach to simplifying the navigation.

Learnings

While the project was largely successful, ongoing feedback has highlighted that some users still struggle to find certain services—particularly the less universal ones. I stand by the decision to simplify navigation by removing buttons that could have caused confusion, but in hindsight, I wish I had captured more structured insights from the testing sessions.

It’s often said that the best way to understand user needs isn’t by asking them directly, but by observing their behaviour and interpreting their actions. Looking back, I wish I had applied this mindset more rigorously when reviewing our testing notes. Due to the intense workload leading up to launch, we didn’t dedicate enough time to a deep analysis of our findings post-testing.

Ideally, I would have set aside time to break down our test notes into clear behavioural insights—examining not just what users saying, but also what they’re doing, thinking, and feeling. This could have provided a stronger foundation for addressing the latest feedback on navigation challenges, helping us refine the user experience even further.